Any commentary on inflation that doesn’t take into account the pandemic is worthless. With the Delta variant and now Omicron, the economy isn’t functioning normally. The virus is limiting the supply of goods and services, while Americans have more disposable income than before the pandemic. Reduced supply and increased demand means inflation. What will happen with inflation after Omicron peaks, sometime in the near future? Nobody knows, but perhaps inflation hysteria isn’t justified?

What the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today:

The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) increased 0.5 percent in December on a seasonally adjusted basis after rising 0.8 percent in November . . . Over the last 12 months, the all items index increased 7.0 percent before seasonal adjustment. The energy index rose 29.3 percent over the last year and the food index increased 6.3 percent.

Increases in the indexes for shelter and for used cars and trucks were the largest contributors to the seasonally adjusted all items increase. The food index also contributed, although it increased less than in recent months, rising 0.5 percent in December. The energy index declined in December, ending a long series of increases; it fell 0.4 percent as the indexes for gasoline and natural gas both decreased. . . .

A brief summary from Catherine Rampell of The Washington Post:

Since Covid began, consumer spending has risen a ton — especially for goods and especially for durable goods. Services up a little since February 2020, but not much.

At exactly the same time goods are in much higher demand, supply chains for goods have snarled. Hence, price spikes.

[Today’s report shows] once again, durable goods (cars, TVs, computers, appliances) in the lead for inflation, at 16.8% year-over-year, not seasonably adjusted.

Nondurables (food, clothing) in 2nd place at 10.2%. Services (travel, healthcare, education) with the least price growth at 4%, in part because so many services remain high risk.

Durables are by definition durable—we don’t need to buy/replace them often. Many expected that demand for durables (and therefore price pressures) would eventually run out of steam; how many fridges can people buy? Durable spending has slowed recently but is still way up compared to pre-Covid.

Maybe the demand for durables fades, supply chains unsnarl, price pressures recede. That would be good. Then the question becomes – what happens to services? Services inflation has generally been lower than goods inflation…but rents (a service) have been rising, and those are “sticky”.

Anther reason to worry that inflation might persist for a while yet, even as supply chains untangle themselves, is inflation expectations. Expectations of higher prices can become self-fulfilling.

An overview and the political context from Rep. Tom Malinowski (Democrat-NJ):

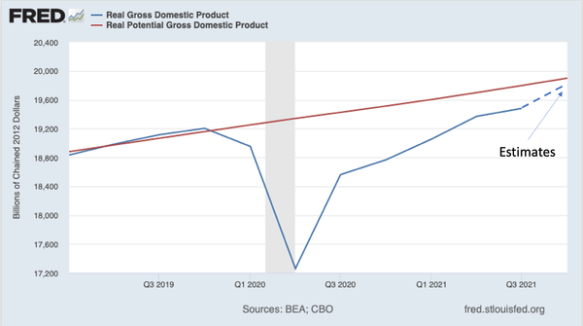

Virtually everyone agrees on the cause of the harmful inflation we’re experiencing: people have more money to spend, but that demand is chasing too little supply. But who we blame and how we propose to solve it reveals a lot about our political divide.

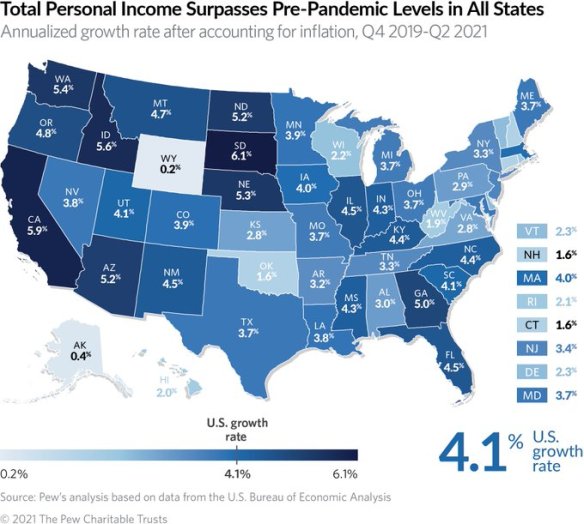

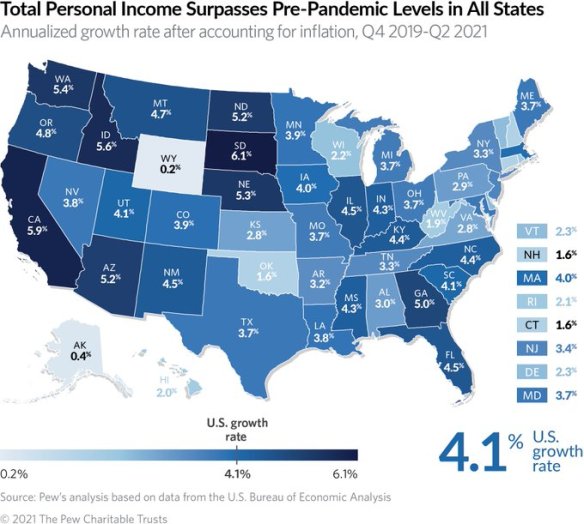

It’s an incredible fact that despite one of the worst economic crashes in our history, average Americans (not just the super rich) have more household wealth to spend today than they did before the pandemic.

Government spending — bailing out small businesses and state & local governments, helping people who lost jobs, stimulus checks & the child tax cut — worked to rescue our economy and left Americans with the extra cash we are now trying to spend (i.e., higher demand).

Had the government not done those things, it’s absolutely true that there would [be less] inflation now.

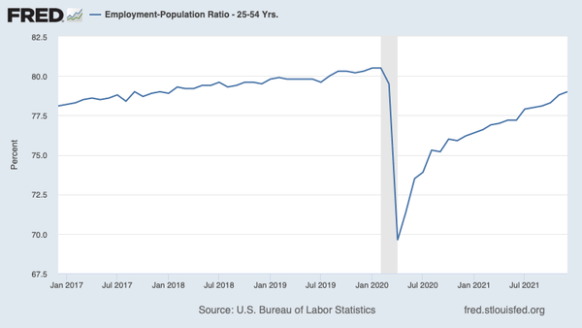

But we also wouldn’t have amazing economic growth with historically low unemployment [and higher wages across the country]. Millions of Americans would be destitute.

So when you hear people blame “Biden spending” for inflation, what they’re saying is that you should have less money to spend . . . that your wages should be lower; that your taxes should be higher; that the government should have let your employer or municipality go bankrupt.

What most Democrats are saying is that increased demand (more people with more money to spend) is a good thing! And that the way to beat inflation is to help the supply of goods and services in the economy to catch up to healthy consumer demand.

We’re focused on improving efficiency of our ports and delivery systems, which helped greatly during the holiday season. Some good news: The port of New York/New Jersey is moving 20%+ more goods than before the pandemic without delays. . . . As Omicron passes in the US, our labor disruptions will ease. But we must also get more people vaccinated in countries where COVID has shut down factories critical to our supply chains.

Crushing COVID is obviously critical to fighting inflation. As Omicron passes in the US, our labor disruptions will ease. But we must also get more people vaccinated in the US and in countries where COVID has shut down factories critical to our supply chains.

If you’re concerned about inflation, you should also support letting employers legally hire people already in the US who desperately want to work the jobs now being unfilled — and back politicians who would rather fix the economy than demonize immigrants.

To sum up: The solution to inflation is not to squeeze middle class Americans as Republicans are suggesting, so that we have less to spend on cars, food, and travel. The solution is to build back supply chains resilient enough to meet American consumers’ post-pandemic needs.

Finally, from The Washington Monthly, how lack of competition (and missing anti-trust enforcement) has made the supply chain so vulnerable:

In recent weeks, senior Biden administration officials have been arguing that monopolization explains at least some of the inflation that is eroding the otherwise impressive wage gains average Americans are experiencing. The case they make is that firms in concentrated industries are using their excessive market power to raise prices and fatten their bottom lines at the expense of consumers. They point specifically to industries like oil and gas and meat processing, where corporate profits are skyrocketing.

. . . In the meat industry, thanks to lax antitrust enforcement, four companies now control 55 to 85 percent of the markets for beef, pork, and poultry. Since the fall of 2020, the price of beef has risen by more than 20 percent, far higher than the inflation rate. At the same time, the profits of the meat-packing industry are up more than 300 percent. Consolidation is hardly limited to the meat industry. It is rampant throughout the economy. So too are recent corporate profit rates . . .

But for argument’s sake, let’s say that . . . predatory pricing by oligopolistic firms isn’t driving the current inflation, but rather, “supply chain hiccups” brought on by pandemic induced labor shortages and high demand. The question is, why were the supply chains so fragile in the first place?

The answer is monopoly—in particular, the hollowing out of capacity as a result of industry consolidation and Wall Street’s demand for short term profits. Consider the case of semiconductors—crucial components in most of the products we use. As recently as a decade ago, America was producing vast numbers of cutting-edge semiconductors right here on our shores. Since then, . . . the federal government has allowed the biggest domestic manufacturer, Intel, to buy up or drive out most of its U.S. competitors. The firm then offshored or sold off its U.S. manufacturing capacity to reduce costs. That boosted Intel’s stock price and delighted investors. But it left the company with scant domestic capacity to increase supply when COVID-19 shut down Asian semiconductor factories. The falloff in semiconductor supply has led, in turn, to shortages of, and higher prices for, everything from cars to cell phones.

Or consider the cargo ships that haven’t been able to get products into and out of U.S. ports. That, too, is a problem exacerbated by monopoly. Ocean shipping was a highly regulated industry until a quarter century ago . . . That led to three vast carrier alliances, all foreign owned, gaining control of 80 percent of the ocean shipping market. These alliances then built super-sized cargo ships that can only dock in a few ports, like the ones in Los Angeles and Long Beach, which now service 40 percent of all U.S. traffic. This highly consolidated system kept shipping prices, and hence overall inflation, low for years. Now, its brittleness is contributing to inflation.

Once supplies do land in U.S. ports, there are not enough trucks and truck drivers to deliver products to our warehouses and stores. In the recent past, however, many of those goods were delivered by freight rail. Why aren’t those goods now moving on trains? Because . . . the federal government allowed the railroad industry to monopolize. And the Wall Street hedge funds that control those monopolies have more recently demanded that they rip up tracks, mothball rail cars, and lay off seasoned union employees to get costs down and stock prices up. Now our freight rail system doesn’t have the capacity to take up the slack. . . .

Of course, it took decades, and countless bad decisions in Washington, for our supply chains to become as concentrated, uncompetitive, and breakable as they are now. It will take years of strong antitrust enforcement and other measures to set things right.

You must be logged in to post a comment.