My immediate reaction to this election was succinct:

Almost half of American voters are creeps or idiots. It’s not polite to say so, but that’s how it looks from here.

I wondered at the time whether I should change it to “creeps and/or idiots”, since that would have been more accurate, but decided to leave it alone.

Alex Guerrero, a philosophy professor at Rutgers University (the state university of New Jersey), offers a similar analysis, but more detailed and nuanced. He ends up at an interesting, although implausible, place:

Four years ago, I wrote that whoever won, half the country would feel “some combination of anger, alienation, shame, sadness, despair, fear, impotence, rage, and hopelessness.” We—the millions of members of the two parties—were far apart then and have moved even further apart under Txxxx.

If you are one of the almost 77 million Americans who voted for Biden, what should you make of the almost 72 million Americans who voted for Txxxx? Let me distinguish two broad views.

The first is to see Txxxx supporters—or at least many of them—as bad like Txxxx: as people who are racist, or xenophobic, or sexist, or don’t mind that Txxxx is; people who spent four years saying “fuck your feelings”; people who don’t mind Txxxx’s willingness to make up electoral fraud and to disregard norms of law and democracy; people who ignore or embrace Txxxx’s cruelties, collusions, corruptions, and crimes. These people might be Txxxx die-hards who worship him, quasi-nihilistic fans who enjoy his talent for enraging the left, or pragmatists who see Txxxx as a cruel but effective means to their ends.

Whichever category they fall in, they are morally culpable for supporting Txxxx—particularly once it was clear exactly who Txxxx is and how he would govern—and likely to be what we might colloquially call bad people. Furthermore, this is not something that is easily changeable. These views and values are now deeply held and unlikely to be modified, at least not in the near future, at least not for the vast majority of them. Call this the moral deplorables view.

The second is to see Txxxx supporters as not nearly as bad as Txxxx himself. These 70 million Americans might be people who have been misled into viewing Txxxx in unrealistic ways: as a patriot, a leader, a staunch ally of Black and Latina/o communities, a religious person who cares about all people, a skilled businessman who can support employment and economic recovery, an ally of freedom and justice. These are people whose values—we are to imagine—are not that different from our own. They are not racists, bigots, or sexists, or not deeply so, and perhaps not much more than many of Biden’s 77 million supporters.

But they have a large set of false non-moral beliefs about Txxxx himself, and another large set of false non-moral beliefs about the views and character and positions of those on the left, including Biden. Let us imagine, further, that those false beliefs themselves are not culpably held—they result from the evidence they have encountered in the echo chambers that they find themselves in, and that they find themselves in these positions is not their fault [Note: in many cases, that’s hard to imagine]. There are more modest and more extreme versions of this view—maybe people are somewhat morally responsible for their false views, rather than being completely off the hook. But the basic view suggests that Txxxx supporters could be productively engaged, that they could change their views. Call this the epistemic reformables view.

(I will leave aside the view that asks us to think that Txxxx himself is not as bad as he seems to be, although of course that is what Txxxx supporters would urge us to think.)

The first view focuses on the deep moral character of Txxxx supporters. The second view focuses on the contingently bad epistemic situation of Txxxx supporters. The correct view probably involves some complex mixture of these.

Many who support Biden will see the moral deplorables view as correct and see the epistemic reformables view as misguided and naïve. The idea of trying to empathize with and constructively engage Txxxx supporters—something that they almost never do for us—is pointless and morally misguided. We are done with the countless thinkpieces that try to understand the disaffected white Txxxx voter. If you support Txxxx, we don’t support you, we aren’t going to try to understand you, we aren’t going to go out of our way to engage you, we are going to fight you tooth and nail, and we are going to defeat you. What that means is not entirely clear. More on that in a moment.

On the epistemic reformables view, we assume that many of Txxxx’s supporters are not as bad as supporting Txxxx would seem to require. Something else must have gone wrong. Many put blame at the doorstep of the misinformation ecosystem that exists on the right, led by Breitbart, Infowars, Truthfeed, OAN, Gateway Pundit and others at the extreme edge, and Washington Examiner, the Daily Caller, Fox News, and others at something somewhat less extreme—all of this swirled together and shared by the output from smaller operations and individuals through Facebook, YouTube, Twitter . . . This is how people end up believing QAnon, how they end up seeing Biden as a “child sniffing, demented liar,” and how they end up thinking everyone in the Democratic party is secretly a socialist (indistinguishable from a communist) hellbent on destroying America.

There are other explanations, too. . . . Their apparently racist and bigoted attitudes are not deep; they reflect lack of education, fear of what is unfamiliar, and being a bit behind rapidly changing social norms. . . .

On this view, the things to push for are reform of our institutions: educational, political, informational [Question: How does one go about reform Fox News?]. With those kinds of reforms, we will come to see that millions of Txxxx supporters are very much like us—people we cannot only tolerate and respect, but also love and embrace. . . .

We will get more information about which view is correct in the coming years as we see how people change (or don’t) in response to Biden’s presidency and Txxxx receding (we can hope) into the background. But when I incline toward the second, one reason is because of the relatives of mine who I know both support Txxxx and, although not perfect people, are not like Txxxx—and I can see how they have come to believe what they believe, even when that seems like a mistake.

If one thinks the first view is correct, one must think about what other moral obligations come along with that view. Among other things, I think that view should come with a commitment to dissolving the United States political community.

If one is elected to represent a political community, one should be committed to taking seriously the preferences and values of the whole community, compromising with (and certainly not just ignoring) views held by large percentages of the population, and making law and policy that is responsive to the full electorate, not just 51% of it. But one should ignore morally deplorable views and citizens who hold such views. But one cannot do so if that means ignoring the views of millions of people in a systematic way. In that context, the options are either a kind of omnipresent moral paternalism or simple political domination—neither is compatible with basic democratic values, at least not if one expects that situation to be durable over time. . . .

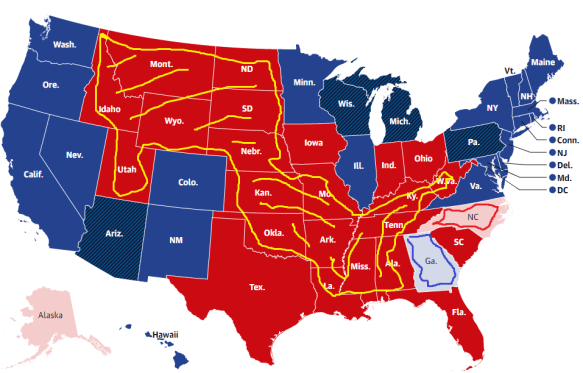

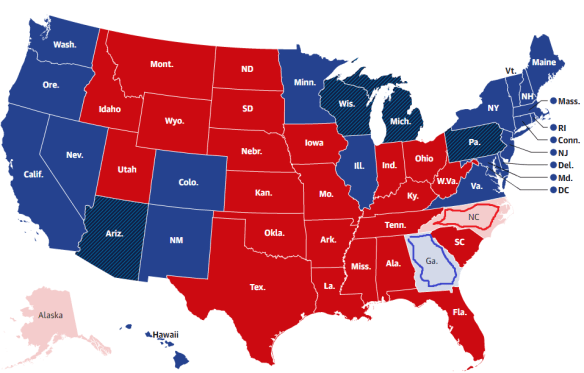

Txxxx got near 60% or more of the vote in the contiguous states of Idaho, Montana, Utah, Wyoming, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Kansas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, and West Virginia. That deep red stripe can pick up other softer red states if they want to join. The Western and Eastern states could be two separate countries, or one. Maybe even raising the possibility results in some change.

Of course, it is true that views do not go away if one simply divides the political community. What one faces then is the situation we are in with respect to many foreign countries with what we perceive to be serious problems—we try to influence them to change and open our borders to those who would like to leave their community and join ours.

To the extent that this response seems excessive, it is perhaps because we still have hope that we are in the epistemic reformable situation. But—I conclude once again, four years later—perhaps we should be more open than we seem to be to talking about whether and why we all want to remain in a country together.

Unquote.

We should keep in mind that preferring right-wing propaganda to reality-based journalism is revealing in itself. For most people, it’s not a totally innocent choice. Also, “informational institutions” like Fox News are not exactly susceptible to reform. I’m less forgiving and less optimistic about these matters than Prof. Guerrero.

As the map shows, the Electoral College result did create three contiguous zones, but for poor isolated Georgia (assuming we consider the Great Lakes more like wide rivers — as far as Georgia is concerned, we could do the same with the Atlantic Ocean).

Aside from the accounting complexity, the main reason against splitting up the United States is that it would condemn millions of people who aren’t creeps or idiots to living in a country run by too many people who are.

You must be logged in to post a comment.