. . . the American republic, originally designed to be a majoritarian representative democracy, has become minoritarian. Or more precisely, at every level of the current institutions of our representative democracy, we have rendered those institutions unrepresentative. This fact alone should be enough to lead aspiring democracies around the world to look elsewhere for models for how democracy might be made to work.

Those are the words of Laurence Lessig, a Harvard law professor, writing for The New York Review of Books. If you want to understand the ways this country has failed at democracy, read what follows. The features of minority rule discussed below include gerrymandered state legislatures and congressional districts, vote suppression, political action committees, the Electoral College, the Supreme Court, the Senate and the filibuster:

What’s most striking about America’s understanding of our own democracy is our ability to see what’s just not there. We are not a model for the world to copy. The United States is instead a failed democratic state.

At every level, the institutions that the US has evolved for implementing our democracy betray the basic commitment of a representative democracy: that it be, at its core, fair and majoritarian. Instead, that commitment is now corrupted in America. And every aspiring democracy around the world should understand the specifics of that corruption—if only to avoid the same in its own land.

The corruption of our majoritarian representative democracy begins at the state legislatures. Because the Supreme Court has declared that partisan gerrymandering is beyond the ken of our Constitution, states have radically manipulated legislative districts. As Miriam Seifter . . . summarized in a recent article for the Columbia Law Review, “across the nation, the vast majority of states in recent memory have had legislatures controlled by either a clear or probable minority party.” Her work was based in part upon an extraordinary analysis published by the USC Schwarzenegger Institute, which found that after the 2018 election, close to 60 million Americans “live under minority rule in their US state legislatures.” The most egregious states in this mix are also among the most important in presidential elections. In Wisconsin, for example, the popular vote for Republicans in 2018 was 44.7 percent; but Republicans controlled 64.6 percent of the seats in the statehouse. Likewise, Republicans in Virginia won just 44.5 percent of the vote but received 51 percent of statehouse seats.

State legislatures, as Seifter characterizes them, are “the least majoritarian branch” of our representative democracy. Yet this fact is all but invisible to most Americans—including, as she evinces, justices on the Supreme Court. We are all outraged when the Electoral College selects a president who hasn’t won a plurality of votes, something it has done five times in its history. Why are we so sanguine about legislatures that are regularly controlled by the party that won fewer votes across the state?

These gerrymandered states then spread their minoritarian poison in two distinctive ways. First, they have taken up the most ambitious program of vote suppression since Jim Crow. Through a wide range of techniques, Republican state legislatures are making it selectively more difficult for presumptively Democratic voters to vote, by reducing the number of polling places in Democratic districts, by ending early voting or voting outside of ordinary working hours, by deploying biased ID requirements that selectively allow forms of identification commonly held by Republicans (gun club registration cards) while disallowing those held by likely Democratic voters (student cards), by understaffing polling places so voters must queue for hours to vote, and by many other creative techniques. In Georgia, the legislature has even made it a crime to give water to people waiting in line to vote. What possible legitimate state interest could that law serve?

These acts are often framed by their opponents in racial terms. That framing is a strategic mistake. I’m happy to stipulate that some who push these techniques of suppression may well be motivated by race—after all, many of the techniques were those of race discrimination before —though most would surely disavow any such thing. But every single person pushing these techniques of suppression is certainly motivated by politics. It is raw partisan power, driven to destroy the electoral prospects of the other party, that explains what is happening here. Before the United States Supreme Court, Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked lawyers from the Republican National Committee why they were opposing provisions enabling more people to vote. Because it “puts us at a competitive disadvantage,” the lawyer was untroubled to reply. How can it be permissible for the party in power nakedly to rig the system against its opponents?

The second way that minoritarian state legislatures spread their poison is by gerrymandering the United States House of Representatives. Partisan gerrymandering was first perfected in its modern “big data” form by Republicans in 2010, and the Democrats then spent the following decade trying to get the Supreme Court to put a stop to it. When the Court announced it would not, there was little left for the Democrats except good government initiatives, aiming at moving the redistricting process away from the most egregiously partisan influences. That did some good—until the 2020 election signaled to Republicans that their party faces virtual annihilation if the majority gets its say. The efforts to gerrymander for 2022 will therefore be the most sophisticated seen yet. Barring a legislative miracle to safeguard voting rights, by the next presidential election Republicans will have secured through gerrymandering the control of the House of Representatives, whether or not they succeed in winning more votes than Democrats. And if the plans of some extremists come to fruition, a critical mass of state legislatures will also have passed laws by then that give them the power to overturn the results of a popular presidential election in their states.

These two techniques of minoritarian rule—gerrymandering and partisan vote suppression—could have been resisted by the courts. Yet what’s striking about the United States Supreme Court is not only that it has done nothing to resist minoritarianism but also that its most significant recent interventions have only ratified perhaps the most egregious aspects of our minoritarian democracy: the influence of money in politics.

While most mature democracies have various techniques for minimizing the corrupting effect of money in politics, the US Supreme Court has embraced the most radical conception of campaign money-as-free speech of any comparable democracy. While the Court has upheld limitations on direct contributions to political campaigns, it has simultaneously held, in its infamous decision in Citizens United v. FEC (2010), that any limitation on independent spending violates the First Amendment. Lower courts have then read Citizens United to mean that any limits on contributions to independent political action committees would violate the First Amendment as well. These rulings together gave rise to the so-called Super PACs that now dominate political spending, and enable strategic coordination of influence that is more effective than spending alone. In 2020, for example, the ten top Super PACs accounted for 54 percent of outside spending.

What’s critical to recognize is that the real power of this money comes not from its effect in persuading voters. Its power comes instead from the dependence it creates within our political system. Candidates know they need the support of Super PACs, either to make the case for them or to defend them from others who would attack. That dependence produces enormous power in the Super PACs concentrated in the hands of a tiny number of very wealthy individuals (who are presumptively but not necessarily Americans). In a nation of hundreds of millions, a few hundred families now dominate political spending.

Here again, there is no shame. In June 2021, the political action committee (PAC) No Labels had a call with Senator Joe Manchin, Democrat of West Virginia, about legislative priorities in the balance of the year. On the call, the founders of the PAC emphasized the power their group had in Washington—not because of their ideas, but because of their money. The ultra-wealthy donors supporting No Labels were able to “hand out $50,000 checks,” its cofounder, Andrew Burskey, bragged. And those checks, he explained, represented the most valuable money in any political campaign. This was “hard” money, money given to candidates directly, which FEC rules allow the candidates to spend themselves. And then to prove just why that money was so valuable, Burskey offered the incredibly revealing picture of just why the economy of influence in Washington gave the ultra-wealthy so much power in Congress. As he explained:

[Most House members] are spending four hours on the telephone, dialing for dollars. And so what [a large contribution from donors] does—aside from sending the very strong message that there are folks who will have your back if you take tough votes that . . . may not be popular within your party—it also in real life frees them to do more work, because it’s spending less time raising those funds.

Burskey is remarking upon the obvious dependence that exists with our current system for campaign finance: the dependence of representatives on fundraising. Because of that dependence, particular kinds of funders—namely, large funders—are especially valuable. Large contributors give members two things at the same time: first, and obviously, money; but second, and even more critically, time. A $50,000 contribution gives members of Congress the chance to breathe, even as it naturally obliges them to [serve] the interests of the person who enabled that chance.

The legislative branch, of course, is not the only minoritarian institution within our republic. Because of the way states allocate Electoral College votes, the executive branch is effectively minoritarian, too. Not just in the most egregious way, when the candidate who wins fewer votes nonetheless becomes the president, but also, and more significantly, in the most regular way: because of the way states allocate their Electoral College votes, it is only a tiny fraction of American voters who actually matter to the ultimate result. All but two states give the winner of the popular vote in their state all of the electors from that state. This means that the only states that are actually contested in any presidential election are the “swing states,” at most a dozen or so of the fifty in the union. Those swing states represent a minority of America—less than 40 percent of the electorate depending on the election. That minority is in turn radically unrepresentative of America itself. The voters in the swing states are older and whiter. Their occupations are more traditional. For example, seven and a half times more people work in solar energy in America than mine coal, yet we never hear anything about solar energy industry workers as an important political bloc in a presidential campaign because those people live in non-swing states like Texas and California. Coal miners live in battleground states, so they become the central focus of the candidates running for president.

It is thus this tiny, unrepresentative minority that effectively selects the occupant of the Oval Office—making the president, as political scientists (such as Douglas Kriner and Andrew Reeves) have shown, especially responsive to this unrepresentative few. Federal spending is higher, all things being equal, in swing states over non-swing states, and regulators are particularly accommodating of swing states’ regulatory concerns. Does America tinker with steel tariffs or ethanol subsidies because either policy makes any sense? No. We live with these policy vagaries because their beneficiaries live in Pennsylvania and Iowa (both swing states).

And so, too, with the courts: if any institution within a representative democracy is supposed to be minoritarian, or at least, counter-majoritarian, courts are. That is true substantively, but it is not supposed to be true politically. Substantively, of course, courts are meant to uphold constitutional rights, regardless of popular majorities. My First Amendment right to speak should not depend upon whether my views are liked by a majority. But the institution of the judiciary is also populated through political action. And to the extent that those actors have power because of a minoritarian corruption of representative democracy, the courts they populate are likewise tainted by minoritarianism.

Consider the Supreme Court: the current bench is divided 6–3, with the majority dominated by extremely conservative justices. That division is in no sense representative of America. Two thirds of the US is certainly not “conservative.” And while the random nature of Supreme Court turnover can sometimes produce such unrepresentativeness, this Court was expressly constructed by Senate leaders who changed the norms of confirmation to effectively steal a Supreme Court seat. In February 2016, then Majority Leader Mitch McConnell declared, after Justice Scalia’s death, that it was “inappropriate” to confirm a nominee of President Barack Obama’s because it was an election year. But when Justice Ginsburg died just six weeks before an election, McConnell declared that it was perfectly appropriate to rush a nominee through the Senate before the 2020 election. In record time (for a modern appointment), Justice Amy Coney Barrett—certainly among the most conservative of the justices now seated on the Supreme Court—was confirmed by a Republican Senate.

Yet, without doubt, the most extreme institution of minoritarian democracy in America today is the United States Senate. Of course, that flaw was in a sense intended: the only way small states were going to agree to the new Constitution in 1787 was if the Constitution gave them extra power. That compromise enraged James Madison, but he could read the political writing on the wall and eventually became a defender of this counter-majoritarian compromise at the heart of our republic.

Even then, though, the minoritarianism built in to the Senate was muted in the first century after the Constitution’s signing. It was muted first because the differences in states’ populations were much smaller than they are today. The largest state in 1790 (Virginia) was thirteen times more populous than the smallest (Delaware). Today, the largest (California) is sixty-eight times more populous than the smallest (Wyoming). But it was muted second, and more fundamentally, because until this century the Senate did not regularly block the will of the majority of senators. The original Senate rules expressly protected the power of the majority, a simple majority, to vote on any bill whenever it wanted. It was only when Senator John C. Calhoun, the proslavery Democrat of South Carolina, began to muck about with those rules fifty years after the Constitution was ratified that the will of the majority was placed in jeopardy.

We miss this fact because the technique of this blocking has a name that has long been part of Senate lore: the filibuster. And given the tactic’s long pedigree, it is easy to imagine that what we are talking about today is the same as existed in the Senate for most of the institution’s history.

The reality is radically different.

The filibuster that existed for most of the Senate’s history was a device that simply slowed the consideration of legislation. It didn’t kill it. The one exception to that characterization was civil rights legislation: the only examples of laws being blocked by filibuster all the way through 1965 were anti-lynching laws, and laws to improve civil rights. For the rest, the filibuster simply delayed the debating and passage of legislation. And for that delaying tactic to operate, the Senators supporting the filibuster had to do real work: if a Senator was to filibuster a bill, he would have to stand on the floor of the Senate and speak, for many hours without a break. Strom Thurmond, Democrat of South Carolina, held the floor for twenty-four hours to hold up the 1957 Civil Rights Bill. That was not mere showmanship as House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s recent eight-hour filibuster was. It was the only way that a filibuster could have any effect.

Today, however, the mechanism of the filibuster is radically different. All a senator must do to assure that a bill is filibustered is make a request to their party leader. That request—which can literally be by e-mail or text—then shifts the bill from being one that will pass if a simple majority supports it to being one that cannot even be debated unless a supermajority of sixty senators supports it.

The effect of the old filibuster was to keep a bill on the floor of the Senate as the filibusterers were debating. That allowed their dissent to be better understood, if not in the Senate, then at least by the public. The effect of the new filibuster is exactly the opposite: its effect is to block any debate until a supermajority allows it. Thus, the For the People Act—a bill that would have reversed much of the state suppression of the vote, ended partisan gerrymandering, and changed fundamentally the way campaigns are funded—has been blocked from debate on the floor of the Senate now twice, even though a majority would vote to allow that debate to occur. This modern filibuster thus doesn’t enable debate or understanding. The modern filibuster is just a gag rule on any legislation a minority does not like.

Even this description, however, masks the real corruption in the system. The norms that limited the filibuster to important issues are gone. Both parties killed those conventions over the past twenty years, the Republicans more aggressively than the Democrats. The filibuster has now become a routine hurdle that any significant legislation must clear. What that means is that we have now introduced a procedural requirement into the passage of legislation that makes the process more institutionally minoritarian than that of any legislature in any comparable representative democracy. Senators from the twenty-one smallest and most conservative states, representing just 21 percent of America, now have the power to block any non-budget legislation.

This filibuster lock alone—setting aside all the gerrymandering in the states, the gerrymandering of Congress, the suppression of the vote in elections, the Electoral College, the corrupting dependence of money—would be enough to categorize America as a “minoritarian democracy.” Like segregationist or sectarian regimes such as South Africa under apartheid, or the Sunni rule of Baathist Iraq, or Syria under the Alawi, the American republic, originally designed to be a majoritarian representative democracy, has become minoritarian. Or more precisely, at every level of the current institutions of our representative democracy, we have rendered those institutions unrepresentative. This fact alone should be enough to lead aspiring democracies around the world to look elsewhere for models for how democracy might be made to work. Our only lesson for these democracies is the consequence of our own failure.

In 1997, after he had surprised the world by winning reelection decisively, Bill Clinton convened a small dinner with the top donors to the Democratic Party at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C. What should he do in his second term? What did they think he could achieve? It was a moment of great hope and possibility—nine months before the revelations of a White House intern would deflect the administration from achieving anything of significance.

As the story is told, about thirty of America’s super-wealthy sat around a table. The president asked each in turn to give him their views. One by one, they rose to speak. The last to rise was a businessman, the founder of Stride Rite Shoes, and the second-largest contributor to the Democrats in 1996. As he stood up, few had any sense of what he would say. When he sat down, few could believe he’d actually said what he did say.

“Mr. President,” Arnold Hiatt began, “I know you’re an admirer of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. So I want you to put yourself in FDR’s shoes in 1940—the year when Roosevelt realized that he was going to have to convince a reluctant nation to wage a war to save democracy. Because that, Mr. President, is precisely what you need to do now—to convince a reluctant nation to wage a war to save democracy.” That would not, of course, be a war against fascists. It would be a fight against fat cats—people like Hiatt, rich people, and people who believed (unlike Hiatt) that just because they are rich, they’re entitled to dinner with the president at the Mayflower. Hiatt was challenging the president to recognize that “current campaign finance practices are threatening this nation in a different, but no less serious way,” he said. . . . There was silence when Hiatt finished. No doubt, some were uncomfortable. . . .

At the time Hiatt spoke, Citizens United was still more than a dozen years in the future. We had not yet seen the pathological gerrymandering of 2010. Few could have imagined the open efforts by partisans in state legislatures to suppress the votes of their political opponents. Not a single Republican in any state legislature was then considering legislation to allow state legislatures to override the popular vote for president. And though the filibuster had been deployed beyond the domain of civil rights by then, it would be nine years before the architect of the modern filibuster, Mitch McConnell, would be elected to lead his party in the United States Senate. And no one—literally, no one—could have imagined an event like January 6 taking place in the United States of America. From our perspective today, Hiatt spoke at a time of relative health in the American democracy. And yet to him, and to many others then—including an eighty-eight-year-old woman who, nine months later, would begin a 3,000-mile walk across the country with the words “campaign finance reform” emblazoned across her chest—the corruption of money was already reason enough to “wage a war to save democracy.”

Today, we confront a Republican Party that has effectively declared war on majoritarian democracy. At every level, the leadership of that party challenges the fundamental idea of majority rule. Rather than adjust their policies to appeal to a true majority of Americans, Republicans have embraced the minoritarian strategy of entrenching what has become, in effect, a partisan, quasi-ethnic group against any possible democratic challenge. They rig the system so the majority cannot rule.

In the face of this threat, what America needs is what Hiatt said FDR had been: a leader who could “convince a reluctant nation to wage a war to save democracy.” Or maybe better, what America needs is a leader like Winston Churchill, who could convince a distracted nation that there is a fundamental threat to our democracy that we must now wage war to save.

Yet we don’t have a Churchill leading this fight. We have a Chamberlain. Rather than name the threat, and rally America against it, President Biden has been keen to negotiate the differences in conciliatory fashion—as if the modern filibuster were not a fundamental threat to democracy and as if the fight against majoritarianism were not a threat either. Biden has been eager to engage in a bizarre nostalgia, recalling a golden age when white men from different parties somehow got along, rather than recognizing that American democracy has never faced a threat like one—even if this is precisely the political reality that Black Americans have known for all of the country’s history.

There was real hope this year for effective action to address this corruption of democracy. Every single major candidate for president in the Democratic Party in 2020 (with the exception of Kamala Harris) had committed to making the For the People Act a top priority in the first hundred days; some had promised even more. Speaker Nancy Pelosi maintained that momentum and passed the act in the House. And after she succeeded in the House, Majority Leader Chuck Schumer committed to getting the Senate to do the same.

Standing in the way, however, was the filibuster.

For most of this year, President Biden defended the filibuster and stood practically silent on this critical reform. He has focused not on the crumbling critical infrastructure of American democracy, but on the benefits of better bridges and faster Internet. Democratic progressives in Congress were little better on this question. Although Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Bernie Sanders, and Elizabeth Warren all supported the For the People Act, in the public eye the issues they’ve championed have overlooked the country’s broken democratic machinery: forgive student debt, raise the minimum wage, give us a Green New Deal…. As a progressive myself, I love all these ideas, but none of them are possible unless we end the corruption that has destroyed this democracy. None of them will happen until we fix democracy first.

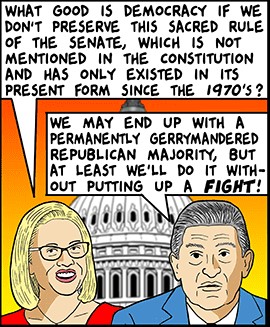

It may well be that nothing could have been done this year. It may well be true that nothing Biden could say or do would move Senators Joe Manchin and Krysten Sinema, the two who are apparently blocking reform just now. Yet we have to frame the stakes accurately and clearly: if we do not confront those imperfections in our democracy, openly and transparently, we will lose this democracy. . . . [i.e. what’s left of it].

You must be logged in to post a comment.