Our former president (hereafter “the defendant”) will be in court tomorrow afternoon to formally be told what crimes he’s accused of. He may be ready to enter a plea of guilty or not guilty as well. It turns out that the proceedings won’t be conducted by the biased and incompetent Judge Aileen “Loose” Cannon, even though she’s been assigned to handle his trial (for now). A magistrate judge, one step below a full-fledged, lifetime-appointment federal judge like Cannon, will be in charge tomorrow. That’s the normal procedure. It’s possible the magistrate judge will set some conditions for the defendant’s release, like telling him not to leave the country. I rather doubt the judge will lock him up.

There’s talk that he’s having trouble finding a lawyer willing to represent him. Would you want to be his lawyer, given how challenging it is to represent him? But he’s already got Florida lawyers who can go with him to court tomorrow, whether or not they represent him in further proceedings.

Judge Cannon being selected to handle this case raises two interesting questions. Why was she selected? Will she step aside or be forced to?

[A personal note/warning: I worked in the Los Angeles County Superior Court system for five years, so may find the following much more interesting than you do.]

Cannon’s assignment was random but not as random as it could have been. The New York Times described the process:

Under the district court’s procedures, new cases are randomly delegated to a judge who sits in the division where the matter arose or a neighboring one, even if it relates to a previous case. That Judge Cannon is handling [the defendant’s] criminal indictment elicited the question of how that had come to be.

Asked over email whether normal procedures were followed and Judge Cannon’s assignment was random, Ms. Noble [the chief clerk of the court] wrote: “Normal procedures were followed.”

Mar-a-Lago is in the West Palm Beach division, between the Fort Lauderdale division and the Fort Pierce division, where Judge Cannon sits. The district court’s website shows that seven active judges have chambers in those three divisions, as do three judges on senior status who still hear cases.

Ms. Noble wrote that certain factors increased the chances that the case would land before Judge Cannon.

For one, she said, senior judges are removed from the case assignment system, or wheel, once they fulfill their target caseload for the year. At least one of the senior judges is done, she wrote, adding that she was highly confident that the other two “are very likely at their target,” too.

In addition, she wrote, one of the seven active judges with chambers in Fort Lauderdale is now a Miami judge for the purpose of assignments. Another is not currently receiving cases.

A third active judge … draws 50 percent of his criminal cases from the Miami division, she wrote, decreasing his odds…. Judge Cannon, Ms. Noble wrote, “draws 50 percent of her cases from West Palm Beach, increasing her odds.”

Given the clerk’s explanation, my rough estimate is that there was a 1-in-4 chance that Cannon would receive the case, assuming the district’s normal process was followed. There could have been as many as 10 judges available, but it turns out there were only 5. In addition, one of those 5 had less of a chance and Cannon had more of a chance, so it was around 1-in-4.

Presumably, Special Counsel Jack Smith was aware of the likelihood that Cannon would get the case, but chose to file the case in Florida anyway, given that the alleged crimes took place in West Palm Beach. I’m pretty sure Smith wouldn’t choose Judge Cannon, given what happened last time she got involved. This is from the same Times article:

The news of Judge Cannon’s assignment raised eyebrows because of her role in an earlier lawsuit filed by [the defendant] challenging the F.B.I.’s search of his Florida club and estate, Mar-a-Lago. In issuing a series of rulings favorable to him, Judge Cannon, [whom the defendant chose to be a federal judge], effectively disrupted the investigation until a conservative appeals court ruled she never had legitimate legal authority to intervene.

One of the mistakes she made was to say the defendant deserved special consideration, since he is an ex-president. That’s not how the law is supposed to work.

The second question is whether Cannon will preside over the pre-trial proceedings and an eventual trial, all of which will go on for months (unless the defendant pleads guilty, is incapacitated, etc.). The New Yorker has an interview with Stephen Gillers, a professor emeritus at N.Y.U. Law and an expert on judicial matters. He says the answer to that question should be “No”, according to the law that covers judicial assignments.

Going forward, what can the government do if it feels like a judge will not give it a fair shake?

It raises the question of recusal. There’s a statute dealing with federal judge recusal—it’s 28 U.S.C. § 455…. The very first sentence … says that a judge should recuse if the judge’s impartiality “might reasonably be questioned.”

Now, the fact that a judge’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned doesn’t mean that the judge is partial. The public may simply not trust the impartiality of the judge. Because public trust in the work of the court is a value as important as the work itself, the rule says that the judge should not sit when we can’t fairly ask the public to trust what the judge does. That rule is especially important in this case. One thing the prosecution can do is move to recuse Judge Cannon on the ground that, in light of her experience in the search-warrant case last year, her impartiality might reasonably be questioned.

And who would make that judgment if the government does push for this recusal?

The judge herself gets to make that decision in our system. If she denies the recusal, the government could go to the Eleventh Circuit and ask it to order her to recuse herself, and that’s a process called mandamus….In effect, you’re suing the judge to force the judge to recuse….

There’s one other thing the government can do, aside from doing nothing, and that is to write a letter to the judge suggesting the reasons she should consider recusing herself without being formally asked to do so. That’s done also, so as not to create a formal motion….

One factor to consider in deciding whether recusal is necessary is how important the case is to the public and to the need for public trust. If the [Court of Appeals] were to reverse Cannon’s recusal decision, one thing they might say is “We are not questioning the probity or the fairness or the competence of the judge, but we don’t think we can ask the public to accept her rulings.”

So, if the government decides that it’s not going to get a fair shake from Cannon based on its previous experience with her, we will end up with this three-judge panel.

Here, the questions are: Will they initially just write a letter suggesting that she recuse? If she does, that’s the end of it. If she doesn’t, will they make a formal motion to recuse? If she grants it, that’s the end of it. If she doesn’t, then they have to decide whether to seek mandamus. If they do, then the three judges, who are randomly chosen and who hear that mandamus petition, will have to decide whether she should be removed. If they decide that she should not, that’s the end of it. If they decide that she should, then there’ll be a reassignment….

Is there some advantage for the government to wait and see how the trial is going before it pushes for a recusal? Would it have a stronger case for recusal that way?

If there is a basis to move to recuse, you can’t wait around. You have to do it quickly. You can’t wait around to see whether the judge rules on motions in your favor.

Are there downsides to going for recusal right away?

The problem with going for recusal right off the bat is that you may lose in the circuit, and now you’re trying a case before a judge you’ve accused of being unable to appear impartial—and that’s not pleasant. So the government may decide that it’s just better to make the strongest case they can and hope that she behaves like a judge.

Given what we saw regarding Cannon’s behavior during the previous case, do you think that the government will or should go for a recusal?

Given the importance of this case, perhaps the most important criminal trial in the history of the United States—certainly the most watched—and in light of what Judge Cannon did in the search-and-seizure case last year, I think she must step aside. I think she must grant a motion to recuse herself, unless she does it before a motion is even made.

And the reason I say that is that she treated [the defendant] as special, or, to put it another way, she was partial to [him] as a former President, which should not have any influence on the way this trial is conducted…. The partiality she expressed in her decisions last year creates a reasonable perception in the mind of a fair-minded person that she is not impartial—which is the test. Her behavior when she was ruling on the search-and-seizure case creates a reason to doubt her impartiality.

But when you say “must,” you mean from an ethical sense.

No, “must” in a rule sense. There’s a rule.

O.K., but there’s also no way to enforce the rule, right?

Except through mandamus.

That suggests to me that [unless Cannon recuses herself] you think the government should or will go to mandamus.

… If the government does so, she must grant the recusal, and if she doesn’t the Eleventh Circuit must order it.

That’s “must” according to the law. Other legal experts have said the same thing. But it’s judges who decide what the laws mean.

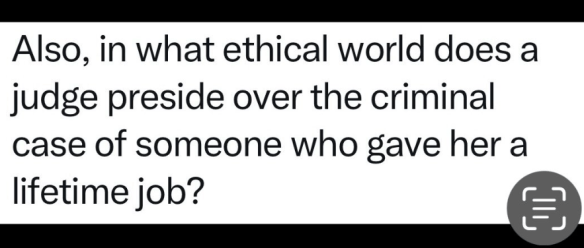

As far as I can tell, the experts aren’t too concerned that the defendant chose Cannon to become a federal judge. Maybe they don’t want to imply that judges tend to favor the politicians who got them their jobs. For us mortals, however, we might ask, as someone did:

You must be logged in to post a comment.