Everyone in the US anyway. Everyone who can read.

Jay Rosen teaches journalism at New York University. From NYR Daily:

“Journalism” is a name for the job of reporting on politics, questioning candidates and office-holders, and alerting Americans to what is actually happening in their public sphere. “The press” is the institution in which most journalism is done. The institution is what endures over time as people come into journalism and drift out of it. The coming confrontation can be summarized thus:

The Republican Party is increasingly a minority party, or counter-majoritarian, as some political scientists put it. The beliefs and priorities that hold it together are opposed by most Americans, who on a deeper level do not want to be what the GOP increasingly stands for. A counter-majoritarian party cannot present itself as such and win elections outside its dwindling strongholds. So it has to be counterfactual, too. It has to fight with fictions. Making it harder to vote, and harder to understand what the party is really about—these are two parts of the same project. The conflict with honest journalism is structural. To be its dwindling self, the GOP has to also be at war with the press, unless of course the press folds under pressure.

Let me explain what I mean by that. The Atlantic’s Ron Brownstein sees the same thing I see. In his recent article on “why the 2020s could be as dangerous as the 1850s,” Brownstein quotes several Republicans who admit what is happening:

The Democrats’ coalition of transformation is now larger—even much larger—than the Republicans’ coalition of restoration. With Txxxx solidifying the GOP’s transformation into a “white-identity party…a nationalist party, not unlike parties you see in Europe…you see the Democratic Party becoming the party of literally everyone else,” as the longtime Republican political consultant Michael Madrid, a co-founder of the anti-Txxxx Lincoln Project, told me.

“Republican behavior in recent years suggests that they share the antebellum South’s determination to control the nation’s direction as a minority,” Brownstein writes. That’s why they went to such lengths to deny Obama a Supreme Court pick and sacrificed everything to get Amy Coney Barrett on the Court. “It’s evident in the flood of laws that Republican states have passed over the past decade making it more difficult to vote. And it’s evident in the fervent efforts from the party to restrict access to mail-in voting this year.” (Add to that list: interfering with the census; crippling the Post Office.)

These events suggest to Brownstein—a journalist who has reported on politics for thirty-seven years—that “Republicans believe they have a better chance of maintaining power by suppressing the diverse new generations entering the electorate than by courting them.” That’s what a counter-majoritarian party has to do: suppress voters, but also project fictions, like the proposition that voter fraud is rampant.

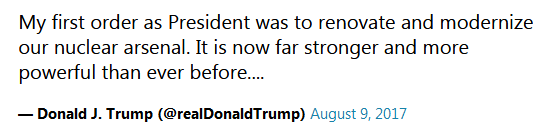

It’s an empirical question: is there a lot of voter fraud in the United States? Does it affect elections? And the question has been answered, not once but many times. So here is what I mean by “the conflict with honest journalism is structural.” The GOP has to rely on fictions like voter fraud to make its case, and if the press wants to be reality-based it has to reject that case.

But how badly does the press want to be reality-based? How far is it willing to go? Forced into it by Txxxx’s flood of falsehoods, journalists routinely fact-check statements like “there is substantial evidence of voter fraud,” and declare them false. And that’s good! But will they stop amplifying strategic falsehoods when powerful people continue to make them? Will they penalize politicians who come on TV to float fictions like that one? Will the Sunday shows quit having them on? And will the press revise the mental image on which its habitual practices rest?

Two roughly similar parties with different philosophies that compete for power by trying to capture through public argument “the American center”—meaning, the majority of voters—and thus win a mandate for the priorities they want to push through the system. On that buried picture of normal politics, the routines of political journalism are built.

There are no routines purpose-built for a situation in which, as Ron Brownstein put it, a minority party, the GOP, is “deepening its reliance on the most racially resentful white voters, as Democrats more thoroughly represent the nation’s accelerating diversity.” There is nothing in the playbook of the American press about how to cover a party that operates by trying to suppress votes, rather than compete for them.

Faced with these kinds of asymmetries, journalists will have to decide where they stand. But the choice for a program like Meet the Press, a network like NPR, a newsroom like The New York Times’s, or a news service like the AP is not which team to join, the Democrats or the Republicans. (Anyone who puts it that way is trying to snow you.) The choice, rather, is whether to continue with a system of bipartisan representation, in which the two parties get roughly equal voice in the news because they are roughly equal contenders for a majority of votes, or whether to redraw their practices amid the shifting reality of American politics, in which the GOP tries to control the system from a minority position—white nationalism for the base, plutocracy for the donor class—while the Democrats try to bring order to their unruly and slowly expanding majority.

Bipartisan fairy tale vs. adjustment to a shifted reality sounds like no choice at all. What self-respecting journalist would not side with depicting the world the way it is?

That seems an easy call, but it isn’t. An observation I have frequently made in my press criticism is that certain things that mainstream journalists do are not to serve the public, but to protect themselves against criticism. That’s what “he said, she said” reporting, the “both sides do it” reflex, and the “balanced treatment of an unbalanced phenomenon” are all about.

Reporting the news, holding power to account, and fighting for the public’s right to know are first principles in journalism, bedrock for sound practice. But protecting against criticism is not like that at all. It has far less legitimacy, especially when the criticism itself comes from bad-faith actors. Which is how the phrase “working the refs” got started. Political actors try to influence judgment calls by screeching about bias, whether the charge is warranted or not.

My favorite description of “protecting against criticism” comes from a former reporter for The Washington Post, Paul Taylor, in his 1990 book about election coverage: See How They Run. A favorite quote of mine from that:

Sometimes I worry that my squeamishness about making sharp judgments, pro or con, makes me unfit for the slam-bang world of daily journalism. Other times I conclude that it makes me ideally suited for newspapering– certainly for the rigors and conventions of modern “objective” journalism. For I can dispose of my dilemmas by writing stories straight down the middle. I can search for the halfway point between the best and the worst that might be said about someone (or some policy or idea) and write my story in that fair-minded place. By aiming for the golden mean, I probably land near the best approximation of truth more often than if I were guided by any other set of compasses– partisan, ideological, psychological, whatever…Yes, I am seeking truth. But I’m also seeking refuge. I’m taking a pass on the toughest calls I face.

I am seeking truth. But I’m also seeking refuge. To me, these are some of most important lines ever written about political reporting in the United States. Truth-seeking behavior is mixed with refuge-seeking behavior in the normal conduct of journalists who report on politics for the mainstream press. That’s how we get reports like this on October 28 from [National Public Radio’s] Morning Edition:

On the right, they’re concerned about the integrity of mail-in ballots. They’re hearing from President Txxxx, who is stoking those fears by claiming, without evidence, that the system is rife with fraud. And on the left, people are worried about another scenario. In their worst fears, Txxxx is ahead on election night and either his campaign or his Justice Department tries to end vote-counting prematurely. And disputes over vote-counting could go on for days or weeks. So activists on both sides are making plans to mobilize.

In this kind of journalism, the house style at NPR, the image of left and right with matching worries is the refuge-seeking part. That Txxxx is stoking fears by claiming without evidence that mail-in ballots are rife with fraud is certainly truth-telling. The point is not that refuge-seeking necessarily injects falsehoods; rather, it is designed to be protective. NPR, the fair-minded observer, stands between the two sides, endorsing the claims of neither. That’s how the report is framed: symmetrically.

But the underlying reality is asymmetric. Mail-in ballots are a safe and proven way to conduct an election. Fears on the right are manipulated emotion and whataboutism. Meanwhile, threatening statements from Txxxx like, “Must have final total on November 3rd” lend a frightening plausibility to the concerns of Democrats. The difference is elided in NPR’s report, which states: “Political activists and extremists on both the right and left are worried the other side will somehow steal the election.” It’s true: they are both worried. But one fear is reality-based and the other is not. Shouldn’t that count for something?

This is how the political scientist Norm Ornstein arrived at his maxim: “a balanced treatment of an unbalanced phenomenon distorts reality.” Again, what self-respecting journalist would not side with depicting the world the way it is? Well, take that NPR journalist conforming to house style, in which truth-seeking is mixed with refuge-seeking, and refuge-seeking often provides the frame due to institutional caution, misplaced priorities, and internalized criticism from an aggressive right.

If we trace refuge-seeking behavior in the press back to its origins in the previous century, we find two main tributaries: a commercial motive to include as many people as possible and avoid pissing off portions of the audience, which rose up as newspapers consolidated, and the professionalization of what had once been a working-class trade, which put a premium on sounding detached and telling the story from a position “above” the struggling partisans. Closer to our own time came a third pressure: the right’s incredibly successful campaign to intimidate journalists by complaining endlessly about liberal bias.

But as Brian Beutler of Crooked Media wrote last week, some things have changed:

Decades of right-wing smears have driven the vast majority of conservative Americans away from mainstream news outlets into a cocoon of right-wing propaganda. Those mainstream outlets have responded [by] loading panels and contributor mastheads with Republican operatives or committed movement conservatives; chasing baseless stories to avoid accusations of bias; adhering stubbornly to indefensible assumptions of false balance; subverting the truth to lazy he-said/she-said dichotomies. None of it can or will appease their right-wing critics, who don’t mean to influence the media, but to delegitimize it. None of it has drawn Fox News viewers and Breitbart readers back into the market for real news.

The right has its own media ecosystem now. As the GOP becomes more devoted to white nationalism and voter suppression, it makes less sense for the public service press to chase that core audience or heed its complaints about bias. Beutler and I are making the same point to mainstream journalists: these are people on the right who want to destroy your institution; it’s time you started acting accordingly.

Making it harder to vote and harder to understand what the party is for are parts of the same project. “Inviting a Republican on to a reputable news show to claim Republicans support pre-existing conditions protections doesn’t offer viewers the Republican position,” says Beutler, “it offers them a lie.” The choice is between truth-seeking and refuge-seeking behavior. That confrontation is coming, whether journalists realize it or not. Even if Txxxx is gone, a minority party with unpopular positions has to attack the reality-based press and try to misrepresent itself through that press to voters. This has been true for a long time. But after Txxxx’s takeover, it is newly unignorable.

. . . There isn’t any refuge anyway, so you might as well shoot for truth.

You must be logged in to post a comment.