Every four years we elect a president. Almost every four years, we discuss the Electoral College. From Jesse Wegman of The New York Times:

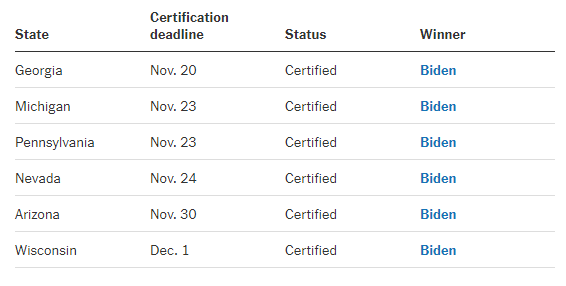

As the 538 members of the Electoral College gather on Monday to carry out their constitutional duty and officially elect Joe Biden as the nation’s 46th president and Kamala Harris as his vice president, we are confronted again with the jarring reminder that it could easily have gone the other way. We came within a hairbreadth of re-electing a man who finished more than seven million votes behind his opponent — and we nearly repeated the shock of 2016, when Dxxxx Txxxx took office after coming in a distant second in the balloting.

No other election in the country is run like this. But why not? That question has been nagging at me for the past few years, particularly in the weeks since Election Day, as I’ve watched with morbid fascination the ludicrous effort by Mr. Txxxx and his allies to use the Electoral College to subvert the will of the majority of American voters and overturn an election that he lost.

The obvious answer is that, for the most part, we abide by the principle of majority rule. . . .

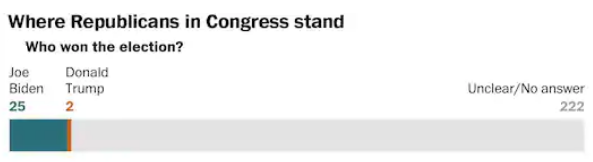

In the last 20 years, Republicans have been gifted the White House while losing the popular vote twice, and it came distressingly close to happening for a third time this year.

Since 2000, we’ve had six presidential elections. The candidate who got the most votes only won four of them. This year, shifting 44,000 votes to the loser in Arizona, Georgia and Wisconsin would have resulted in a 269-269 tie in the Electoral College. That would have moved the election to the House of Representatives, where each state’s delegation gets one vote, regardless of population. Since most states have Republican-majority representation in the House — even though the House has more Democrats — DDT would have presumably been re-elected, hard as that is to imagine.

Among the comments the Times article received, one person said the Electoral College is fine, since we’re a collection of states, the United States of America, not a collection of citizens. He said it’s only fair that we pick a president based on which states the candidates win, not how many votes they get. Besides, he added, votes in the Electoral College are “roughly” assigned by population.

I don’t agree that because we’re called the United States, we should ignore majority rule when it coms to picking a president. After all, the states we live in are supposed to be “united”. But his statement about the Electoral College being “roughly” based on population made me wonder.

How would the 2020 election have turned out if votes in the Electoral College were “precisely” assigned by population, instead of “roughly”? Today, the largest state, California, gets 55 electoral votes and the smallest state, Wyoming, gets 3. But California’s population is 68 times Wyoming’s. So if the Electoral College were precisely allocated by population, California would get 204 electoral votes, not 55. Quite a difference. The next largest state, Texas, would get 150 instead of 38.

Would that have made the result in the Electoral College much different? It was surprising to see that it wouldn’t. If you do the same precise arithmetic for all 50 states and the District of Columbia, Joe Biden receives 974 electoral votes instead of 306 and DDT gets 730 instead of 232. That looks like a big difference, but the percentages are about the same. Biden would get 57.2% of the electoral votes with the precise arithmetic and 56.9% with the rough arithmetic. It works out that way because some big states, like California and New York, went for Biden and some, like Texas and Florida, went for DDT. When you average it all out, the Electoral College result would be about the same either way.

There would be a big difference, however. Big states would be much more important in the Electoral College than small states. If California got 204 electoral votes instead of 55, it would make even less difference who won a bunch of little states like Wyoming, Vermont and Alaska. In fact, assuming precise arithmetic, the 25 largest states would get 1,423 electoral votes vs. 288 for the 25 smallest.

What this shows is that the current Electoral College is significantly skewed to benefit smaller states. Voters in those states play a bigger role than they should, based on how few of them there are. Being precise about population wouldn’t necessarily change the winner every time, but a more accurate Electoral College would reflect where people actually live in these “united” states. It would also reflect the cultural divisions in this country, since smaller states tend to be more rural.

Unfortunately, it’s not just the Electoral College that is skewed toward smaller states. According to the Constitution, each state gets as many votes in the Electoral College as it has members of Congress. Wyoming gets three electoral votes because it has two people in the Senate and one in the House of Representatives. California gets 55 electoral votes because it has two senators and 53 representatives in the House. If seats in Congress were precisely allocated by population, California would still have two senators, but it would elect almost four times as many members of the House of Representatives as Wyoming. The ratio in the House would be California’s 202 to Wyoming’s one, not 53 to one.

If the makeup of the House of Representatives isn’t unfair enough, consider the US Senate. Each state, regardless of population, gets two senators. It was designed to give small states the same representation as big states, so each state, regardless of population, gets to elect two. Maybe that made sense when there were only 13 states and they were relatively close in population. Now we have 50 states with a very wide range of populations.

In 1790, for example, the largest state, Virginia, had 13 times as many people as the smallest, Delaware. Today, as noted above, California has 68 times more people than Wyoming. Furthermore, the 50 members of the Senate from the largest 25 states represent almost 275 million people. The 50 senators from the smallest 25 states represent 49 million.

The imbalance is made even worse by the fact that the Senate is responsible for approving nominations to the Executive Branch (including all the officials in the president’s cabinet) and the federal judiciary (including the Supreme Court), as well as approving treaties. Because of the way senators were to be chosen, the authors of the Constitution assumed that members of the Senate would be more responsible than the unruly members of the House of Representatives. That’s hardly the case today.

In addition, smaller states, which tend to more rural, tend to vote for Republicans. Of the 25 largest states, 15 voted for Biden and 10 for his opponent. Of the 25 smallest, 10 voted for Biden and 15 for the other guy. That’s why the Senate is where progressive legislation goes to die and liberal nominees fall into comas waiting to be approved.

Add this all up and it’s easy to see that a Constitution written in 1789 doesn’t work very well for a large, complicated country in 2020. The Senate is skewed to benefit smaller, more Republican states, while the House of Representatives and the Electoral College, which chooses the president, are skewed the same way, although less so. This unfairness explains why Hillary Clinton could beat her opponent by 3 million votes and lose, why Joe Biden could beat the same opponent by 7 million votes but not necessarily win, and why forward-looking legislation that would make the United States a much better place to live has so little chance of success. Maybe shifting demographics will eventually help, but in the short run, we have to assume the United States will be subject to minority rule from Washington in important ways and much too often.

You must be logged in to post a comment.