If there’s one thing it’s hard to predict, it’s the future. (So, apparently, Yogi Berra once said.)

That didn’t stop Prof. Paul Krugman from writing about the future of interest rates in his New York Times newsletter (I’m leaving out most of his charts):

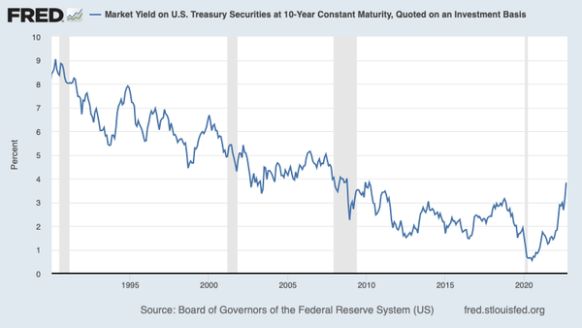

From a financial point of view, 2022 has, above all, been the year of rising interest rates. True, the Federal Reserve didn’t begin raising the short-term interest rates it controls until March, and its counterparts abroad acted even later. But long-term interest rates, which are what matter most for the real economy, have been rising since the beginning of the year in anticipation of central bank moves.

These rising rates correspond, by definition, to a fall in bond prices, but they have also helped drive down the prices of many other assets, from stocks to cryptocurrencies to, according to early indications, housing.

So what will the Fed do next? How high will rates go? Well, there’s a whole industry of financial analysts dedicated to answering those questions, and I don’t think I have anything useful to add. What I want to talk about instead is what is likely to happen to interest rates in the longer run.

Many commentators have asserted that the era of low interest rates is over. They insist that we’re never going back to the historically low rates that prevailed in late 2019 and early 2020, just before the pandemic — rates that were actually negative in many countries.

But I don’t see that happening. There were fundamental reasons interest rates were so low three years ago. Those fundamentals haven’t changed; if anything, they’ve gotten stronger. So it’s hard to understand why, once the dust from the fight against inflation has settled, we won’t go back to a very-low-rate world.

Some background: The low interest rates that prevailed just before the pandemic were the end point of a three-decade downward trend:

What do we think caused that trend? Some commentators say that it was artificial, that the Fed kept pushing rates down by printing money. But basic macroeconomics says that this shouldn’t be possible: If you keep rates artificially low for an extended period, the result should be high inflation. And until the price surge of 2021-22, inflation stayed subdued year after year.

A useful concept here, going back more than a century to the work of the Swedish economist Knut Wicksell, is that of the so-called “natural rate of interest”. Wicksell defined the natural rate either as the interest rate that matched saving with investment or as the rate consistent with overall price stability. These definitions are actually consistent with each other: An interest rate that is too low, so that investment spending exceeds the supply of savings, will cause inflationary overheating of the economy.

And the fact that we didn’t see inflationary overheating over the course of a 30-year trend of falling interest rates suggests that the decline wasn’t artificial — that the natural rate must have been falling over that period.

Why might the natural rate have declined? The most likely culprit is a decline in investment demand, driven by a combination of demographic and technological stagnation.

The key insight is that investment spending is driven in large part by growth — growth in the number of workers and in technological progress. A growing labor force needs more office space, more houses, and so on; a stagnant work force only needs to replace structures and equipment as they wear out. Technological progress can also contribute to investment by making it worthwhile to replace outmoded capital goods, and also by making people richer so they can demand more living space, and so on; if technological progress slows down, investment spending tends to fall.

Since the 1990s, both of these drivers of investment lost a lot of their momentum.

Once the last of the baby boomers reached their mid-20s, the number of Americans in their prime working years, which had risen rapidly for decades, flattened out:

This demographic downturn was even stronger in other wealthy countries. The working-age population in Europe has been declining since 2010, and it has fallen in Japan at a fairly rapid clip.

Technological change is harder to pin down, but it’s difficult to escape the sense that major innovations are becoming increasingly rare…. And for what it’s worth, estimates of total factor productivity, a measure meant to capture the economy’s overall technological level, have grown slowly since the mid-2000s:

So is there any reason to expect either demography or technology to be more favorable for investment in, say, 2024 than they were in 2019? I don’t see it.

It’s true that there has been a lot of recent technological progress in green energy, and it’s possible that an energy transition, helped by Joe Biden’s climate policies, will contribute to investment in the years ahead. But that aside, the same factors that kept interest rates low before the pandemic still seem to be in place.

What about inflation? Another old principle in thinking about interest rates is the Fisher effect, which implies that an increase in expected inflation should normally lead to an equal rise in interest rates. And inflation has spiked in the past year and a half.

That spike is, however, probably temporary. There’s a huge amount to say about inflation, but the 30,000-foot view goes like this: During the pandemic slump, governments gave households huge amounts of aid to maintain their incomes in the face of economic lockdowns. This meant that consumer purchasing power remained high despite a temporary reduction in productive capacity, causing a surge in prices — and leading central banks to hike rates to bring inflation back down.

But there doesn’t seem to be much question about whether they will, in fact, control inflation. Certainly, financial markets expect inflation to revert to pre-pandemic norms:

In summary, then, low interest rates weren’t artificial; they were natural. And it’s hard to see anything that will cause the natural rate to rise once the current inflation spike is over. So the era of low interest rates probably isn’t over after all.

Unquote.

Prof. Krugman may be underestimating the effect of progress in green technologies and how much work will be needed in order to implement them. He may be underestimating the effects of the worsening climate crisis. Or advances in artificial intelligence or biotechnology or nuclear fusion. Or the benefits of advanced technologies given to us by visitors from another world.

But if the recent trend continues, interest rates will go down again. Since interest rates affect both borrowing and saving, and thereby the world’s economy, that’s interesting.

You must be logged in to post a comment.